Hraschina meteorite

| Hraschina | |

|---|---|

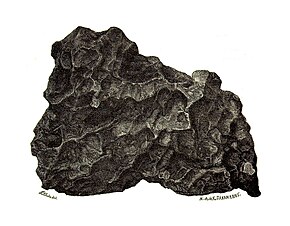

Drawing of the main mass | |

| Type | Iron |

| Structural classification | Medium octahedrite |

| Class | IID |

| Composition | Fe 89%, Ni 10.5%, Ge 89.4 ppm, Ga 74.5 ppm |

| Country | Croatia |

| Region | Hrvatsko Zagorje |

| Coordinates | 46°06′N 16°20′E / 46.100°N 16.333°E[1] |

| Observed fall | Yes |

| Fall date | 26 May 1751 |

| TKW | about 49 kg[1] |

| Alternative names | Agram, Hrascina, Hrasina, Zagrab, Zagreb, Zagrebačko željezo[1] |

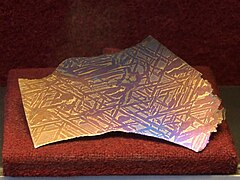

Etched slice with Widmanstätten patterns, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien | |

Hraschina is the official name of an iron meteorite that fell in 1751 near the village of Hrašćina in Hrvatsko Zagorje, Croatia.[1][2] This meteorite is important because it was the first fall of an iron meteorite viewed and reported by a significant number of witnesses,[3] despite its low remaining total known weight.[2] The Hraschina meteorite also proved that rocks really can "fall from the skies".[4]

History

[edit]

On 26 May 1751, at 18:00, a fireball was seen over Hrašćina and sounds like detonations were heard as far away as Varaždin, giving an estimate of nearly 1,000 square miles (2,600 km2) of area over which the meteorite's sound was audible.[3] Many people taking their Sunday evening walk witnessed the event. Baltazar Adam Krčelić, a clergyman, historian, and a noted chronicler of daily events, who was spending time in the village of Biškupec, recorded the following:[5]

"In Biškupec near Varaždin [...] an unusual phenomenon like a small cloud was seen — although it was not a cloud — which became paler and paler, produced an explosive sound and then dispersed. In their ignorance, the common folk thought that the heavens had opened.

Iron masses of 39.8 kilograms (88 lb) and 9 kilograms (20 lb) fell to the east of Hrašćina and were later recovered. The larger mass penetrated 1.40 metres (4 ft 7 in) into the ground.[3] But there are reports that it went much deeper.[4] The smaller mass was split at the place of the fall and partly used by the local villagers for making nails,[6] while the rest of it was split further in Bratislava and subsequently lost.[3]

The Zagreb Catholic chapter sent the meteorites and an official report (the "Protocol of Bishop Klobuczezky and Curate-General Wolfgang Kukuljevic") to the Empress Maria Theresa. The meteorites were deposited in the Treasury in Vienna and then to the Court museum, now the Naturhistorisches Museum Wien (Museum of Natural History in Vienna).[7]

On the basis of the Protocol of Bishop Baron[8][9] Klobuczezky[10] and the fact that these fresh fallen meteorites presented a molten metal crust, in 1794 Ernst Chladni proposed that meteorites have their origins in outer space.[11] Since meteorites were thought to be of volcanic origin, this was a very controversial statement at the time,[12] but in 1803 was confirmed by Jean Baptiste Biot and was then accepted.[13]

In 1808 Count Alois von Beckh Widmanstätten discovered the Widmanstätten patterns by heating a slab of this meteorite.[4][13][14] "Though another scientist, G. Thomson, had also discovered the texture, Widmanstätten's work was recognized by Carl von Schreibers (then Director of the Vienna Natural History Cabinet) and the term Widmanstätten has been used to describe the texture ever since."[13]

Composition and classification

[edit]

Hraschina is an iron meteorite chemical type IID, structural class medium octahedrite.

Composition: Fe 89%, Ni 10.5%, Ge 89.4 ppm, Ga 74.5 ppm, Ir 13 ppm.[15]

Samples distribution

[edit]The main mass (39 kilograms (86 lb)) is conserved at the Naturhistorisches Museum Wien.[13] The second largest mass is a piece of 44 grams (1.6 oz) recently discovered within an old collection. Other pieces are: 20 grams (0.71 oz) at MiN of Berlin, 9.8 grams (0.35 oz) at the Natural History Museum of London, and a few smaller pieces in other institutions.[2] The largest mass shows evidence of a spirited attack with a hammer-like object.[2]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Meteoritical Bulletin Database: Hraschina

- ^ a b c d Horejsi, Martin. "Hraschina put the H in Historical!". Meteorite-Times Magazine. Martin Horejsi's Meteorite and Tektite Books. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Report of the Thirty-First Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. London: John Murray. 1862. pp. 32–33. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Hraschina". Historic Falls. Archived from the original on November 15, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- ^ Marks, Ljiljana (June 2001). "Baltazar Adam Krčelić: Chronicler of Everyday Life" (PDF). Narodna Umjetnost. 38 (1). Zagreb: 140. ISSN 0547-2504.

- ^ "Meteoritsko slavlje u Hrašćini" [Meteorite celebration in Hrašćina]. Vjesnik (in Croatian). 18 May 2011. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ Török, J. (1882): A Magyar Birodalom meteoritjei (II. rész). Természettudományi Közlöny, 14, 495–514.

- ^ (Croatian) Hrvatska provincija uršulinki rimske unije

- ^ (Croatian) Veritas - Samostan sestara uršulinki u Varaždinu Archived 2013-07-01 at archive.today

- ^ (Croatian) Vlatka Vukelić: Povijest sustavnih arheoloških istraživanja u Sisku od 16. stoljeća do 1941. godine, doktorski rad, Zagreb, 2011.

- ^ Chladni, Ernst, Über den Ursprung der von Pallas gefundenen und anderer ihr ähnlicher Eisenmassen und über einige damit in Verbindung stehende Naturerscheinungen (On the Origin of the Pallas Iron and Others Similar to it, and on Some Associated Natural Phenomena)

- ^ Williams, Henry Smith (1904). "5". A history of science. Vol. 3. New York: Harper. p. 168ff. ISBN 0-250-40142-8.

- ^ a b c d Martel, L. M. V. (May 2009). "Better Know a Meteorite Collection: Natural History Museum, Vienna, Austria. Planetary Science Research Discoveries". Hawai‘i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- ^ McCall, Gerald Joseph Home; Howarth, Richard John (2006). The history of meteoritics and key meteorite collections: fireballs, falls and finds. Geological Society. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-1-86239-194-9. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ Natural History Museum (2000). Catalogue of meteorites: with special reference to those represented in the collection of the Natural History Museum. Vol. 1 (5 ed.). London, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 243. ISBN 9780521663038. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

External links

[edit]- "Hraschina". Historic Falls. Archived from the original on November 15, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- The meteorite collection of the Natural History Museum, Vienna

- Proslava obljetnice pada metorita u Hrašćini (in Croatian)